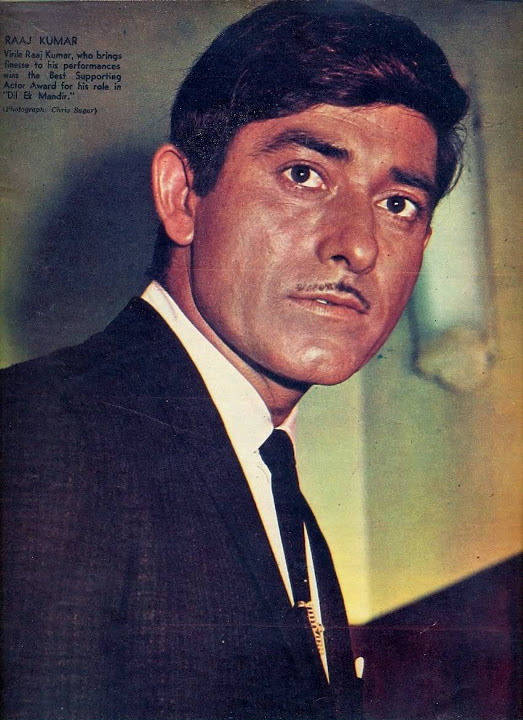

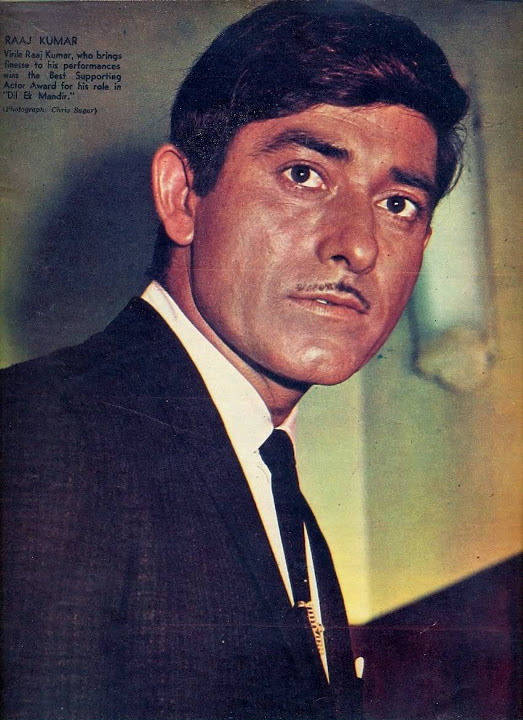

Image obtained from Karen Bandal’s ‘Everything Bollywood’ blog.

Raaj Kumar is probably my favourite bollywood actor. While I appreciate the work of several of his contemporaries, and the substantive contribution they made to the cinema of their time, Raaj is the only one I’ve ever felt strongly about. Certainly, in terms of his overall body of work and the number of good films he was a part of, he falls well behind Dilip Kumar or Dev Anand. But sometimes it takes only one powerful performance to leave a strong impression, and win someone’s lasting admiration and loyalty. For me, that performance came in ‘Pakeezah’. I fell head over heels for the ‘Salim’ of Pakeezah, and sometimes when you love a character so much, at least some of that love is transferred on to the actor. Raaj did full justice to his role in ‘Pakeezah’. Indeed, ‘Pakeezah’ would not have been what it is, with any other male lead being cast as ‘Salim’.

“Badal kar fakeero ka hum bhes e Ghalib, tamashae ehle karam dekhte hain” / “By donning guises, we, Ghalib, view the spectacle of another’s generosity”

Best Films

Thus began my fascination (obsession) with Raaj Kumar. I started digging up on his other films, and have now seen almost all of them (or if the film is too awful to watch I’ve at least seen the parts of the film where Raaj is present). I think that Raaj Kumar’s best film’s apart from ‘Pakeezah’(1972) are ‘Dil Apna aur Preet Parai’ (1960), ‘Paigham’ (1959), and ‘Godaan’ (1963). I loved him as the reserved, reticent ‘Dr. Sushil Varma’ silently in love with his nurse ‘Karuna’ (Meena Kumari) in ‘Dil Apna aur Preet Parai’, or as ‘Ram Lal’ the honest, hard-working but unperceiving mill worker in ‘Paighaam’. The former film was really lovely, but would have been even better if the love between Dr. Varma and Karuna had been allowed to deepen and flourish and take a new route, without the film devolving into your regular love triangle story, in which Dr. Varma’s obnoxious wife is predictably despatched off in the end. It remains, however, a well written film, where the quiet romance which develops between Dr. Varma and Nurse Karuna is lovely to watch. There are some heart-warming hospital scenes which feature good performances by the rest of the cast. ‘Dil Apna aur Preet Parai’ also has some wonderful songs.

Dr. Sushil Varma

with ‘Karuna’ (Meena Kumari)

‘Paigham’ (1959) is a didactic, semi-socialist, strongly ‘message-orientated’ sort of film. Its makers did not intend it to be a work of art, and it isn’t one. Yet, I absolutely consider ‘Paigham’ to be a genuinely good movie; being well-written, tightly constructed and showcasing some very good performances. Ram Lal (Raaj Kumar) works hard to provide his younger brother Ratan (Dilip Kumar) with a college education. Ratan who returns to his home town after graduating (with distinction) secures work as chief mechanic/engineer (his position is somewhat ambiguous) in the local mill. Ram Lal is employed in the same mill as a labourer. Ratan percives that the mill workers are being deprived of the wages they are entitled to, and there is also indifference on the part of the management towards their safety and conditions of work. He seeks to establish a worker’s union to demand change and represent the workers claims. The more traditional minded Ram Lal, a good but uneducated man, takes issue with the course of action Ratan proposes. It strikes him as dangerously confrontational, and for him smacks of disloyalty towards their employer. The film engages with the tussle between the two brothers as to what constitutes rightful conduct, in line with the developments at the mill. Ratan’s sweetheart Manju (Vyjayanthimala) is also employed as secretary in the mill. Ram Lal strongly objects to Ratan’s association with her, as her paternity is unknown. This exacerbates the conflict between the brothers. It’s really a movie about the kind of India the makers of the film aspired to see; socialist (yet democratic), equitable, just and relatively classless. Dilip, Raaj and Vyjayantimala do a wonderful job, and I think that Pratima Devi who plays the mother of Ram Lal and Ratan is very good as well (as she was in Dil Apna aur Preet Parai). Pandharibai, the sweet faced lady who plays Ram Lal’s wife is also good. In both films Raaj gives excellent performances, and is highly convincing and natural in his respective roles.

Ratan is welcomed home by the family

Ram Lal and Ratan each exhort the workers towards their respective positions

I will speak at greater length about ‘Godaan’ (1963). Being Raaj Kumar’s own favourite film amongst the seventy odd movies he was a part of (1) it deserves special space, and while I thought it was a good film with brilliant performances by both its leads Raaj Kumar and Kamini Kaushal, my reaction towards ‘Godaan’ was in some respects quite mixed. The film is based on Munshi Premchand’s 1936 novel of the same name. The novel ‘Godaan’ is widely regarded as a masterpiece of Hindustani literature, and at core concerns Hori (a village peasant) and his wish to procure a cow. The film depicts the exploitative propensities of the zamindars or landlords of the time, as well the oppressive caste dynamics then (and even now) prevailing particularly in rural settings. The hypocrisy of the priestly class, as well as that of the zamindars and money lenders is amply demonstrated in the film.The press book of Godaan, released in 1963, states the following:

“Go-Daan is the tragic life story of Hori (Raaj Kumar), a true peasant of India. He is a fatalist who has become so, facing crisis after crisis in his dealings with money lenders and the richer classes. And he dies like most men, with an unfulfilled desire. He dies without owning a cow, “The Goddess of Wealth in the House” as the peasants call it…the cow that can be given away in Go-Daan (“Cow-Gift”) after his death.”

Raaj Kumar as ‘Hori’ in Trilok Jetley’s 1963 ‘Godaan’

My only issue with this description is that Hori appears to be a fatalist right from the outset, before disaster upon disaster strikes him. He obstinately and obtusely refuses to acknowledge wrong in others, when they actively harm him, repeatedly exploit him, fraudulently appropriate his few possessions (while his family is in dire straits), and penalise him for the sense of humanity he retains and they are devoid of. At the beginning of the film Hori procures a cow on loan which his younger brother poisons out of jealousy, the money lenders apply extortionate rates of interest on loans and cook up the accounts against him. The Village Panchayat levels a huge fine on Hori and his wife Dhaniya for sheltering the lower caste girl who is bearing their grandchild. Hori and his wife stand by the girl ‘Jhuniya’ in the face of the Panchayat’s opposition, but they are made to pay the price. In order to pay the fine, Hori procures further loans and thus begins a never-ending cycle of burgeoning debt… and this is a very incomplete list of Hori’s afflictions and problems.

What is frustrating is Hori’s standard response to every calamity that comes his way. He automatically reconciles himself to the conduct of those oppress him, without a shade of protest. For him, it is all fate, and there’s nothing you can really do about it. Hori’s perspective is that he and his family belong to a particular ‘biradari’ or community, and they have to bow before its norms, however unfair. His more discerning and spirited wife, sees right through those who exploit Hori and pose as his well-wishers, and obviously finds Hori’s persistent refusal to defend either himself or his family, maddening. The present order seems profoundly unjust to her, and even Hori’s son Gobar smarts under the strong inequalities engendered by the social arrangements in place. They cannot rationalise these things to themselves, or resign themselves to it all, as Hori can. Right towards the end of the film Hori and his family are almost destitute; all they have is some land that is to be forcibly sold off to pay the mountain of debt that has accumulated. The village priest visits Hori and presents a proposal whereby Rupa (Hori’s youngest daughter) will be married off to the well-to-do but elderly Ram Sevak. The marriage will cost comparatively little for Hori, and they will be able to retain their land. Finally, Hori is disgusted, and his wife Dhaniya is outraged. He says:

Kahan woh thoos bhurra aur kahan meri phool si Rupa! Aaj mere aise din agaye hain ki aap mujhe larki bechne ko kehte hain?

‘That old man and my flower of a girl Rupa! Are times so bad for me, such that you come here asking me to sell my daughter?’

Hori is pained, but here again, as with everything else, he soon begins to reconcile himself to the idea. Thinking aloud to Dhaniya, he says:

Ram Sevak bhurra toh nahi, haan adher zaroor hai. Rupa ke sukh likha hai toh yahan bhi sukh uthayegi , dukh likha hai toh kahin bhi sukh nahi paa sakti.

‘Ram Sevak is not quite old, though he is middle-aged. If contentment is written for Rupa she will find it with him as well, if sorrow is written for her, then she will never find contentment anywhere.’

Dhaniya: var kanya jodh ke hon tabhi byah ka anand hai

‘If the groom and bride are well matched, only then can we anticipate happiness from the marriage.’

Hori: Byah ka naam anand nahi pagli, tapasya hai. Tapasya.

‘The name of marriage is not happiness. Marriage is trial, trial.’

Hori’s initial reaction to Ram Sevak’s propasal for Rupa

Rupa is accordingly married off to Ram Sevak. The land is not sold, but the debts remain and in a short space of time, Hori works himself to death. At the time of Hori’s death, Dhaniya only has one rupee and four annas in her possession which she gives for the Go-daan (or cow-offering). She brings this to the preist, and as Hori’s funeral rites are being performed, we hear in Mukesh’s soulful voice the following refrain:

Aas adhuri (Unfulfilled aspirations)

Pyaasi Umariya (A thirsty age)

Chaaye Andhera (Clouding darkness)

Sooni Dagariya (A lonely pathway)

Darat Jiya Bechain (A pained restless heart)

Darat Jiya bechain (A pained restless heart)

O Rama (O God)

Jarat Rahat din Rain (Eyes perpetually awake)

There is a certain rawness, pain and power in Mukesh’s voice (which he has further modulated to sound like Hori/Raaj Kumar), which here brought tears to my eyes. These poignant lyrics were penned by Anjaan, and are so apt a summation of Hori’s life; his unfulfilled aspirations, his thirst, the clouding darkness, the lonely pathway he has had to tread, his eyes perpetually open with strain and anxiety; slumber is a luxury.

Hori collapses while working in the fields. Poor Dhaniya thinks that Hori has gone for good. Kamini Kaushal gives a superb performance in Godaan.

The film was made by Trilok Jetley with passion and dedication. The Go-Daan press book states that it had been Jetley’s dream for some years to make a film adaptation of the novel ‘Godaan’, and he paid the highest figure which had ever been paid then for book rights in India, for the purposes of film adaptation. Months were spent on the script and the services of Pandit Ravi Shankar were recruited for the film’s soundtrack. It’s a pity that a film made with such care should have flopped so miserably at the box office. But, I am not surprised that it fared badly. I am not saying this because I don’t think ‘Godaan’ is a good film. It is a good film, but it makes for a very bleak viewing experience.

I don’t know if it’s exactly the same in the book, but there is also the issue of predictability. When any calamity comes Hori’s way, you know precisely what will happen. Poor Dhaniya, who knows exactly what’s going on and is raging inside, will urge Hori to defend himself, while Hori will seek to avoid confrontation at literally any cost, resign himself to the injustice, and attribute what is happening to fate. At times Dhaniya tries to take unilateral action, but her efforts are undone by Hori. I would have found ‘Godaan’ more interesting had there been some variation in Hori’s responses or some evolution in his outlook. It wasn’t necessary to take him the point where he could think and act like Dhaniya, but his mode of thinking remains uniform throughout. He is exactly the same at the end of the film as he was at the beginning. Perhaps this is precisely the point Munshi Premchand is trying to impress upon us in his novel, decades of systemic oppression, and the ideology that is rammed down the throats of peasants, by those on the upper rungs of society (whether the zamindars or the priestly class) has led to a sort of paralysis in thought, and fear of stepping outside the externally demarcated boundaries, to the point where one afraid to be honest with themselves. One can also think of Hori’s state as a fixed internalisation of the norms which have been dictated to his from the earliest stages of his life. I’m also aware that things which seem axiomatic and self-evident now, such as human equality and freedom to enjoy though fruits of your own labour, weren’t actually that self-evident in the time and place this book depicts. Even so, perhaps I simply don’t have enough contextual knowledge to be able get into Hori’s psyche and really understand his frame of mind. For this reason and others I ‘ve just got myself a copy of the novel ‘Godaan’, am keen to read it, and may do a separate post on it.

The novel is a pretty large book which features many more characters than those which appear in the film. Understandably, Jaitley has cut it down to deal with the core story which chronicles the trials of Hori and his family. Some of the more educated, prosperous characters which appear in the book also appear in the film. ‘Rai Saheb’, the big zamindar of the village who also exercises functions akin to that of mayor, ‘Miss Malti’ (a social worker), ‘Mr. Mehta’ (an academic and philosopher) and ‘Mr. Mirza’ (another social worker) all feature in the film. Rai Saheb makes fine speeches about how he will be the last one to protest if zamindari goes, and talks about how wrong it is for wealth to be generated on other people’s broken backs. Yet, he continues to live very lavishly and actually pockets the fine which is levied on Hori for offering protection to the lower caste girl Jhuniya. Most of the talk between the better educated classes is conducted in shudh Hindi, and the exchange of ideas which take place between Miss Malti, Mr Mehta and Rai Sahab was largely lost on me. Another reason to read a translated copy of the book.

Raaj Kumar himself has to say about ‘Godaan’:

“Godan’ is the best film I ever acted in. It gave me full scope to get into the skin of a rural character and emote like a villager genuinely does. As it was based on a Munshi Premchand masterpiece, I got my scope to deliver” (2)

I would differ to the extent that I don’t think of ‘Godaan’ as Raaj Kumar’s best film ever, but the rest I agree to. Both Raaj Kumar and Kamini Kaushal are really excellent in their respective roles. Raaj very effectively projects Hori’s vulnerability, fatalistic outlook and internal resignation. Raaj Kumar is younger than the ‘Hori’ of Premchand’s novel, but by affecting a stoop and exuding a sense of fatigue, Raaj manages to look the part. Strangely, the bulky Mehmood doesn’t look too odd playing his son ‘Gobar’ and also gives a good performance. In the song ‘Hiya Jarat Rahat Din Rain’ Hori, having recently recovered from physical collapse through overwork, views his surroundings; the land and the animals grazing upon it with their offspring. Suddenly, there enters into Hori the exuberance of a young man (and Raaj looks great in this song). Walking along he comes across the skeleton of a cow and is both visibly distressed, and reminded of his aspiration to have a cow. Raaj emotes wonderfully in the song, which has been very feelingly sung by Mukesh. You can see it at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vE6-PqX6jhA

Better Films

Amongst the better films of Raaj Kumar are ‘Oonche Log’ (1965), ‘Phool bane Angaare’ (1963), ‘Pyar ka Bandhan’ (1963) and ‘Hindustan ki Kasam’ (1973). These films are not favourites, but they are pretty decent films, in which Raaj gives good performances….and I love Raaj when he acts naturally, before he permanently succumbed to a more theatrical and exaggerated mode of acting later on in his career. In ‘Oonche Log’ Raaj is a conscientious police officer and the film projects the dynamics at play between him, his wayward brother ‘Rajnikant’ (Feroz Khan) and their father ‘’Major Chandrakant’ (Ashok Kumar) a retired Army major. Major Chandrakant’s outlook is somewhat aligned with that of Srikanth’s (Raaj Kumar), but his behaviour is sometimes reminiscent of a certain feudalism which his son Shrikant finds repugnant and rejects (e.g. Major Chandrakant thinks that whipping servants is a wholly legitimate and appropriate means of addressing lapses in conduct).

‘Oonche Log’

‘Pyar ka Bandhan’ (1963) does draw on a number of clichés, is rather melodramatic in parts and Raaj’s acting is occasionally exaggerated in it. Still, I liked him as ‘Kalu’ the hard-working tange-wala, and devoted elder brother of ‘Sona’ (Kumari Naaz). In ‘Pyar ka Bandhan’, because of his father’s early demise Kalu cannot pursue an education, and becomes a ‘tange wala’ (horse cart driver) to support his ailing mother and younger siblings. He works selflessly and tirelessly to give his younger sister Sona the education he never had, and later to ‘get her married’ to the boy of her choice. In valourising Kalu’s exertions to give his sister a grand wedding party, the film reaffirms the understanding that weddings need be a lavish affair, and that this should appropriately be financed by the bride’s parents or relations. While the arrangement of a dowry often isn’t explicitly adverted to in movies, this theme of conscientious brother striving ‘get his sister married’ is one that has been common in Indian films until very recently, and unfortunately continues to be strongly reflected in Indian society. Kalu’s ultimate motivation in all this is, however, securing his sister’s happiness, and the film is another one of those strongly ‘message-orientated’ movies so common around this time; It emphasises the importance of equal opportunity, female education, and the desirability of creating a classless society. However, I do think that the film’s makers could have shown more foresight in eschewing the need for a grand wedding at all, and thus removing the factor underlying many of Kalu’s worries, and a root cause of a lot of gender discrimination in India.

As ‘Kalu’ the tange-wala in ‘Pyar ka Bandhan’

Captain Rajesh courting Usha (Mala Sinha) in ‘Phool bane Angaare’

Both ‘Phool Bane Angaare’ (1963) and ‘Hindustan ki Kasam’ (1973) are war films. In ‘Phool bane Angare’ (I rather like the name: flowers turn to sparks of fire) Raaj plays the part of Captain Rajesh in love with Usha (Mala Sinha), a caring, independent spirited girl who undertakes to support and provide for her widowed mother and younger brother. Mala Sinha (who had me wincing and cringing all through ‘Mere Huzoor’) does a pretty decent job in this film, and the depiction of their initial courtship is quite nice. Rajesh is subsequently called to serve in Korea (am slightly confused about this; initially it appeared that the war in question was the Sino-Indian war of 1962), while Usha remains tending after her mother and brother. This movie is about duty towards one’s family and one’s country in times of crisis, and like ‘Pyar ka Bandhan’, ‘Phool bane Angaare’ isn’t a bad film. ‘Hindustan ki Kasam’ (1973) focuses on the conduct of Operation ‘Cactus Lily’ which took place in the backdrop of the Indo-Pakistan war of 1971. Not being very familiar with Indian Military history, I really don’t have anything to say about the film’s depiction of the war and operation ‘Cactus Lily’, but the film appears to be free from any kind of jingoism. It’s director Chetan Anand goes to considerable lengths to show the essential humanity of the other side, and this is not done in a merely tokenistic fashion. ‘Hindustan ki kasam’ is also notable in that it probably features the last completely natural and unaffected performance Raaj was to give in his career. Because it’s a Chetan Anand film, Raaj’s love interest, to my chagrin, is Priya Rajvansh. The film is rather far-fetched in the second half, but I’m still inclined to place ‘Hindustan ki Kasam’ in Raaj Kumar’s ‘better films’ category.

Returning from a test flight in ‘Hindustan ki Kasam’

Best Known Films

Apart from ‘Pakeezah’ (1972), ‘Mother India’ (1957),‘Waqt’ (1965) and possibly ‘Heer Ranjha’ (1970) are Raaj Kumar’s best known films. ‘Mother India’ is not a movie I personally like much, but it is widely considered to be a landmark film, and while Raaj played a somewhat peripheral role in it, the movie shot him to fame and really got his film career going. Raaj, like many other members of the cast, engages in a fair bit of over-acting in ‘Mother India’. The songs are however wonderful, and Raaj, despite a few bad wigs, is eye-candy in the film. I don’t really think he needed a wig at this stage, given that three years later, in ‘Dil Apna aur Preet Parai’ he sported his own hair and looked very handsome. ‘Waqt’ likewise has always struck me as being a nothing film; all glitz and glamour and very little underneath. In 1965, ‘Waqt’, with its strong glamour quotient, may have fascinated audiences, but I don’t know how it keeps contemporary viewers stuck to their seats. Even on a purely ‘masala’ level, I don’t feel that ‘Waqt’ makes for an entertaining viewing. But again, Raaj is eye-candy in it. ‘Mere Huzoor’ (1968) is, I think, a pretty awful film; very artificial, cheesy and affected, in the spirit of most of the 1960’s ‘Muslim Social’s’ that preceded it. However, because Raaj looks the way he does, I can watch it repeatedly just for him (or rather repeatedly watch the parts where he is present), to the exclusion of everything else (lol…even to the exclusion of what Raaj’s character is actually saying). Other points in favour of the film are Johnny Walker and Manorma, who are both very funny in it.

Shamu and Radha in better times (Mother India)

Seeking to charm her Highness (Waqt)

‘Heer Ranjha’ (1970) was a laudable attempt by Chetan Anand to make an a epic film on the fabled lovers of the Punjab; Heer and Ranjha. What is unique about the film is that it is entirely in rhyme. It’s evident that Chetan was trying to offer viewers something novel by recruiting Kaifi Azmi to pen the film in verse. I actually wonder whether Chetan would have been more successful in conveying this tale if he had just stuck to prose, albeit poetic prose. I don’t think that just making things rhyme necessarily elevates the script to the level of poetry. This is not a judgement of Kaifi Azmi’s broader literary abilities (I love a number of the song lyrics he has written, though I haven’t read his poetry or other substantive works apart from this). It is just my response to the script he penned for the film ‘Heer Ranjha’. I thought the script was all right, without being anything amazing. What really destroyed ‘Heer-Ranjha’ for me was Priya Rajvansh. Priya Rajvansh may have been a very nice person in real life, but she was an absolutely atrocious actress, and did not at all look the part of Heer. Indeed, I can say without exaggeration that she is the worst Bollywood actress I have ever watched. The are so few films where Raaj really got to play the romantic hero, and I love him in full-on romantic mode. Indeed, here he acted wonderfully as Ranjha, but to see him have to romance Priya Rajvansh : ( Her being cast as Heer made a film I would have otherwise probably enjoyed, unwatchable. I have mostly just seen those frames of the film where Priya is absent. The film also features some lush cinematography and good songs.

Ranjha thinking of Heer

His Appearance

With reference to Raaj’s looks, just surfing on the net, I have read a few unflattering appellations being used for him. He has variously been described as ‘Mr. Twisted Ears’, ‘irritating’ or just plain ‘odd’ looking. The truth is prior to ‘Pakeezah’ I never really did consider him particularly handsome, at least not in the conventional sense, and kind of understood where the ‘irritating’ description came from. But, with ‘Pakeezah’ his looks grew on me, and now I am totally on the same page as those who regard him as downright gorgeous. Moreover, then I hadn’t seen any of his earlier films from the 50’s and early 60’s where he was really handsome. He had aquiline, rather chiselled features, and could project an attractive intensity on the screen when he chose to. For me, he’s also the first man to sport a moustache who doesn’t automatically start looking like an ‘uncle’ because of it. I wish I could see him in his earliest films ‘Rangeeli’, ‘Aabshar’ and ‘Ghamand’. Chances are these won’t be very good films, because Raaj was a new comer then, and probably took whatever came his way. But still, I’d love to see such a young Raaj Kumar.

Decline

Post 1973 came a very steep decline in the kind of films Raaj acted in, and the kind of performances he gave. It’s not as though Raaj hadn’t been a part of bad films before this (indeed, he had his fair share of bad film’s in the 50’s and 60’s as well). What is unusual is how consistently poor these films were, and how they represented a whole new level of awfulness. Raaj, how could you say yes to something like ‘Karmayogi’??..Ughhhh…yuck! Almost his entire output in the 80’s and 90’s was uniformly terrible. ‘Police Public’ (1990) strikes me as being a marginally better film, but is not what you would call a good movie. Many of these films, even a hard core Raaj Kumar fan like me, cannot sit through (It’s really difficult to even sit through just the parts of the film which feature Raaj Kumar). Granted the 80’s were a bad decade for movies, but even then I find most of Raaj’s choices, in this period, utterly unfathomable. From what I have read about him, it appears that he was an intelligent, intellectually inclined man and must have known that most of these films were total trash…Why then did he consent to act in them? His acting in these films, moreover, was often very exaggerated and affected. Any excuse for this? This is what Raaj himself has to say:

“….Another film which I really enjoyed working in was ‘Oonche Log’ where I played a police inspector. The story was really brilliant but astonishingly both the films (Godan and Oonche Log) flopped badly. People only wanted me to deliver high voltage dialogues and I was forced to adopt a particular style to cater to the audience…Yes, I know none of my present films have the touch of my earlier classics like ‘Mother India’, ‘Godan’ or ‘Pakeezah’. But I have to survive as acting is my only profession. Today the standards of films have really deteriorated a lot and no director is interested in making a serious film like Mehboob Khan, B.R. Chopra or Kamal Amrohi.” (3)

Basically Raaj is saying that films were his bread and butter, and he had to make do with whatever came his way….Still Raaj, I hardly think you would have starved to death if you had said no to movies like ‘Desh ke Dushman’, ‘Jung-Baaz’ or ‘Galiyon ka Badshah’ (shudder)….I don’t know how you saw your own films without groaning, shutting your eyes and covering your ears. When going to his worst films of the 80’s and 90’s on youtube, I see comments saying things like ‘Raaj Kumar is the KING!’ or ‘Kya Dialogue Delivery Hai!’ Apart from financial reasons, there’s a real chance that Raaj allowed responses like this to get the better of his own judgement.

A still from ‘Karmayogi’ (ughh) . Seriously Raaj, WHY?

Raaj Kumar: The Man

I really know far too little about the man himself, to be able to provide any real insights here. As stated, from what I have read about him, it appears that he was an intelligent, well-educated and intellectually inclined man. Raaj Kumar, originally Kulbushan Pandit was born in Loralai (now in Pakistan) in 1926 (some articles say 1927).He came from a large family of nine children. Raaj recalls “I knew no loneliness since I come from a big family. We never needed any outside entertainment. We used to sing, dance and fight in our home”. His father was an Army officer, and the family originally hailed from Kashmir. (4) A recent “documentary” about Raaj Kumar was made, which was actually really awful, and just consisted of the presenter showing footage of his films ( footage easily available to anyone with internet access) and regurgitating verbatim the content of old (and pretty poor) internet articles on him. (5) Scarcely any actual research was conducted. They did, however, also briefly interview his son, and he provides some interesting snippets about his father. Kulbhushan graduated with an Arts degree from the then prestigious Government College in Lahore. He won a gold medal in philosophy, and wanted to go on to study English literature at Oxford. For whatever reason, this didn’t eventuate, and after working for some time as a sub-inspector at the Mahim police station in Bombay, he turned to films. Raaj Kumar’s son Purru speaks of how well before his actual entry into movies, Khulbushan was approached by Sohrab Modi, who wished to cast him as the male lead in an upcoming production. Because Khulbushan was then still interested in heading to Oxford to study literature, he refused the offer. Raaj Kumar discusses how he subsequently entered films in this video interview: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cSDHoB4TBiA

From the above interview in the link provided, it’s evident that Raaj was a very articulate man. A Cineblitz article states “Like any of his stock, he was extremely well read and was knowledgeable on a myriad of subjects. He also had a flair for many languages — English, Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi and Kashmiri”. (6)

In the late 1960’s he married Jennifer, an Anglo-Indian air-hostess whom he met on a flight, while travelling to a shooting destination for ‘Heer Ranjha’. It was love at first sight, and after marriage, he named her Gayatri, in accordance with her kundali. Though Purru states “basically, we’ve been brought up in all faiths. We’d visit churches, dargahs, mandirs and synagogues”. (7) It appears that Raaj was very possessive and protective about his wife and children, and sought to keep them out up the public eye as much as possible. I feel like I myself am now just repeating the content of the interviews I have read…It’s probably best for me to just provide links below to all of these interviews. When I first became strongly interested in Raaj Kumar (over a year ago now) there was almost nothing about him on the internet. Now, a reasonable, if not abundant, amount of information has cropped up on him. It appears that many considered Raaj to be an egotist, and in fairness, that egotism does come out pretty distinctly in a number of his interviews. It also turns out he was scarcely ‘Mr. Shareef’ in real life and before he married Gayatri, was something of a playboy. With reference to his reputation as an ‘eccentric’, I think that Raaj Kumar was an interesting enough man in himself without having to play the part of the ‘eccentric’, whatever his motives (warding off the press, keeping his private life private by creating an alternative external persona, or just grabbing a bit of attention at parties). In this 1983 Filmfare magazine interview, I think the interviewer K.N.S. probably gets it right when he makes the following observations:

“He seems to enjoy building a maze around him through which it is difficult to move and find the real person. He seems to forget people’s names. His comments, at least as quoted, are brash and provocative. What emerges from these is a composite of someone unpredictable and nearly insufferable. In reality, at least at very close quarters, he is quite a caring person when he wants to be one. He has his loyalties and affections. He has his own code of chivalry and honor. His courtesy is faultless. Perhaps at one time he felt misused or ill-used and started building mental self defenses.” (8)

Well Raaj, you weren’t perfect but there were a lot of great things about you. I still know so little about you, and wish I could know more….I wish I could have met you, and told you what an impact your performance in ‘Pakeezah’ had on me. I sometimes imagine scenarios whereby some strange transfiguration of time, I happen to take the seat next to you on a flight or train journey, and then ensues an extended four hour conversation….and in this imagined conversation you obviously aren’t completely indifferent to me. You don’t throw me off with platitudes, but I get to hear what you genuinely think, and we talk and talk about films and books and all kinds of things. You were a very special actor, and are really special to me (ok….now this is getting super lame, but I can’t help myself). When given a decent script to work with you could really show your acting prowess. In many of your films though, there wasn’t much opportunity for you to show your talents, or extend and test your own abilities as an actor. Your overall range probably wasn’t that broad; I can’t really imagine you doing comedy well, but perhaps I’m just saying this because I haven’t really seen you do comedy. After all, just because I haven’t seen it doesn’t mean it can’t be. Within your perceived range, you were a unique actor, had an appealing individualistic style, and could give subtle expressions. In the very few romantic roles you did, you exuded a warmth and tenderness and restrained passion on the screen which felt very real. Unfortunately, a number of the movies you were a part of didn’t really demand the subtlety, nuance and finesse you could bring to a performance (acting qualities amply demonstrated in films such as ‘Pakeezah’, ‘Godaan’, ‘Dil Apna aur Preet Parai’ and even ‘Heer Ranjha’)…but you were something wonderful; there are no two ways about that. ©

(1) Ranjan das Gupta, ‘The True Avatar of Mother India’, Friday Review Delhi, The Hindu. 11/7/2008. See: http://www.hindu.com/fr/2008/07/11/stories/2008071150810300.htm

(2) Ibid

(3) Ibid

(4) ‘Raaj Kumar: Memories’ obtained from ‘Cineplot’ (Published in Cineblitz, August 1996). See: http://cineplot.com/raaj-kumar-memories/

(5) NewsX, ‘Falshback: Remembering Raaj Kumar’. See http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jH4g6hy1Y9A

(6) Farhana Farook, ‘Dad was Bizarre but never boring- Purru Raaj Kumar’. Filmfare (28/01/2013) See: http://www.filmfare.com/interviews/dad-was-bizarre-but-never-boring-purru-raaj-kumarr-2214.html

(7) Ibid

(8) ‘Raaj Kumar’. Interview by K.N.S. in 1983. Obtained from ‘Cineplot’. See: http://cineplot.com/raaj-kumar-interview/

Recent Comments